Of course, when

producer-director Dori Berinstein documented an entire Broadway season,

she had no idea that what she was filming would be such a dramatic,

surprising and exciting year as 2003-2004 was. That was the season that:

Rosie O’Donnell decided to become a Broadway producer and dragged

across the Atlantic a modest little musical that had caught her fancy

in London. By and about Boy George, it was plainly marked

“Taboo,” but

she did it anyway, believing that, given her wealth and high public

profile, she could will the show into place. Unfortunately, she

had not figured on friction among the show’s creators that tied her

hands and doomed the project. Nor were matters helped by a hostile

press, which reported (sometimes gleefully) every backstage body-blow.

(One montage in the film flips through a blitzkrieg of bitchy

headlines, to the tune of Boy George’s plaintive lament, “Do You Really

Want To Hurt Me?”) Through it all, O’Donnell high-roaded it, even after

this ambitious caprice had devoured her whole $10 million investment.

A pleasant, if decidedly bizarre, little enterprise about puppets that

fornicate and have sexual-identity issues--

“Avenue

Q”--surfaced

Off-Broadway at the Vineyard Theater and, buoyed by a

better-than-average reviews, bolted for Broadway to try and make a go

of it there. As composer Robert Lopez notes in the film, “It started

out as a joke, sort of--puppets singing funny songs--and it turned into

something that actually has a heart.” An impish ad campaign kept

the show afloat until Tony time when it went into election-year

overdrive, urging voters in big red, white and blue lettering to “vote

with your heart.” Nobody thought it would work (and, in a sense, it

didn’t because Tony voters are not so simply swayed), but it turned out

to be--in one of the most startling Tony upsets ever--the little “Q”

that could. As producer Robyn Goodman so eloquently put it when she

picked up the prize for Best Musical: “It certainly doesn’t suck to be

us tonight.”

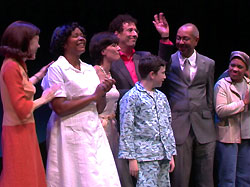

A veritable armada of deep-pocketed producers rallied behind the

commercial lost-cause called

“Caroline, or

Change” and brought it up

from The Public Theater downtown to Broadway, no doubt with dreams of a

Pulitzer dancing in their heads. Tony Kushner, its author, had, after

all, brought most of them the Pulitzer with his “Angels in America,” so

they were right to hope that lightning would strike twice. It didn’t

and closed at a loss after five struggling months, only to reopen again

in Los Angeles to rave reviews. It’s the show in which Tonya Pinkins

went Public again, resurfacing in the star spot after a bitter divorce

and child-custody battle sent her scurrying out of the limelight. An

act of personal courage, her performance of a black maid in backwoods

Louisiana of 1963 was bravura work and widely regarded as a shoo-in for

a Best Actress Tony. Again, it didn’t happen.

At a whopping $14 million (that looked it!),

“Wicked”

was the year’s

most expensive and anticipated musical event--so its stumble with

reviewers when it left the starting gate was doubly conspicuous, but

the paying customers quickly countered those critical yawns, and the

show has been raking in a million or more every week since opening. The

secret of its success? That it purports to be the backstory of The

Wicked Witch of the West from “The Wizard of Oz,” and audiences are

drawn like magnets to that beloved source by L. Frank Baum.

Sympathetically reinvented, that witch is named Elphaba after the

author’s initials and played lime-green by Idina Menzel, whose first

spray-painting (a ritual she endured for more than two years) is caught

here by the cameras. It was a bitter pill for “Wicked” to lose to

“Avenue Q,” which was capitalized at a quarter of the cost.

The making, unmaking, remaking and survival of these four musicals are

explored with remarkable candor in "ShowBusiness: The Road to Broadway," a feature-length

documentary which, because of the unprecedented cooperation its

creators received from the theater community, looms like the ultimate

in inside-Broadway movies. But this quartet hardly constitutes the

whole picture of the season. Punctuating the narratives of these shows,

pitched in like confetti, are other openings, other shows. The

2003-2004 stage season was also a time when:

Hugh Jackman took Broadway by storm, playing a fellow Aussie (the late

Peter Allen) in “The Boy From Oz” and doing it with such spectacular

panache and showmanship that he put the kibosh on the critical carping

about the musical’s bio-book. He never missed a performance and sold

out constantly. A Tony was the least the community could do.

In contrast, Donna Murphy set some kind of dubious record for poor

attendance because she was ailing during the re-run of “Wonderful

Town.” Eventually, the producers brought in as replacement Brooke

Shields, who--surprise, surprise--charmed the pants off critics.

Actresses of color completely dominated the Tony Awards--three blacks

and a green. Phylicia Rashad became the first African American to win

the Tony for Best Actress in a Play, and Audra McDonald became the

first to win four Tonys (a distinction she shares with Angela Lansbury

and Gwen Verdon). Both were cited for the Sean Combs-driven revival of

“A Raisin in the Sun.” A sleeper contender for Best Featured Actress in

a Musical, Anika Noni Rose, emerged victorious, but Tonya Pinkins who

played her mother didn’t come through as predicted, losing to that lady

in green, Idina Menzel.

In non-musical matters--and there were

nonmusicals on Broadway (not many and not nearly enough, but some)--it

was the first time that two Pulitzer Prize winners came up for the Best

Play Tony in the same year: Nilo Cruz’s “Anna in the Tropics” and Doug

Wright’s “I Am My Own Wife.” The winner was the latter, a one-man,

multi charactered, fact-based saga about Charlotte von Mahlsdorf (born

Lothar Berfelde), a gentle but resilient German transvestite who

survived both Nazi and Communist regimes. It was the first time a solo

work received the Tony for Best Play. Jefferson Mays, who executed all

of the roles, won the Best Actor prize. It was reported that when his

name came out of the envelope, Christopher Plummer (nominated for his

“King Lear”) exited in a huffy hurry.

That was the kind of year

it was, and wasn’t it – and aren’t we -- lucky to have Dori

Berinstein’s cameras around to catch it?

-- Harry

Haun